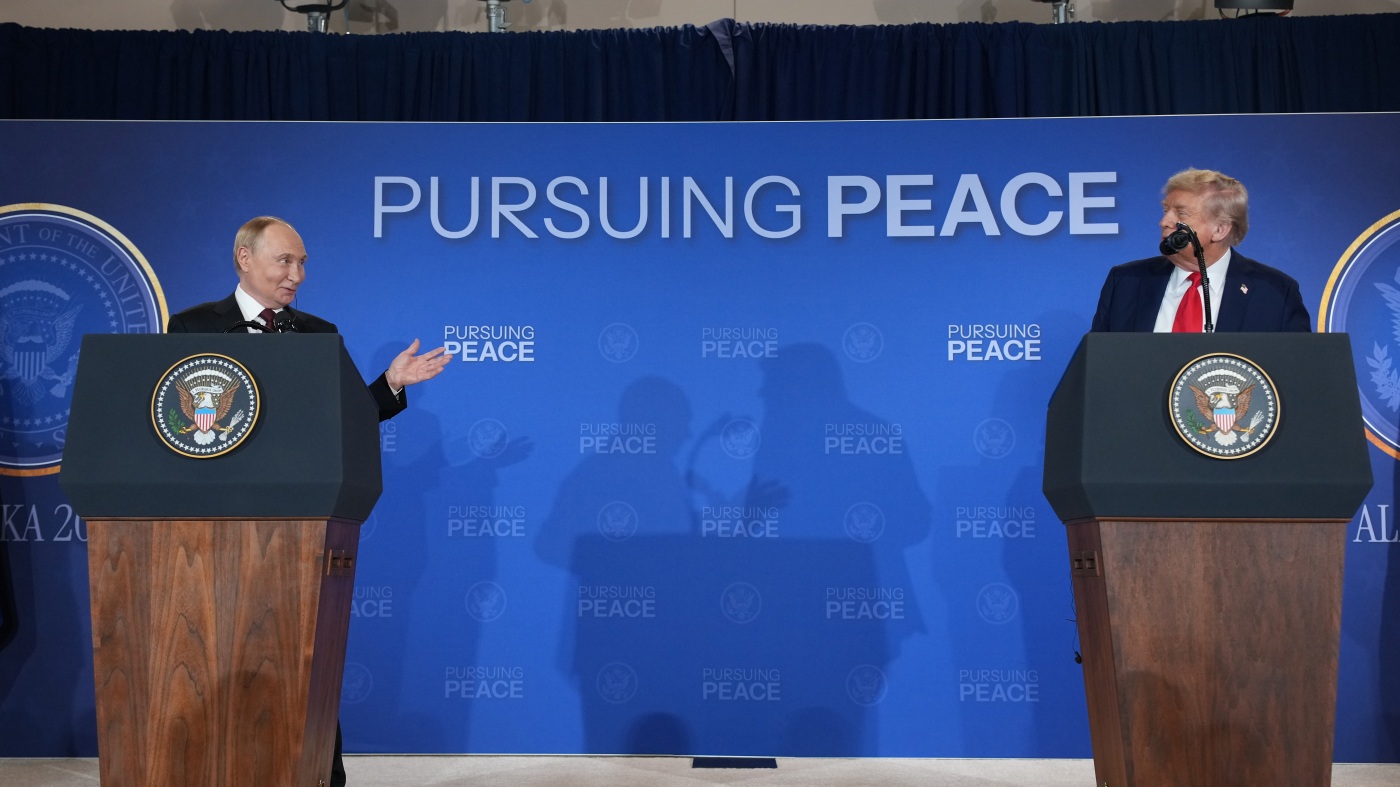

Much has been made of the kabuki show in Alaska between Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin. Many experts and keen current affair followers were expecting a ceasefire agreement, others expecting a meaningful peace agreement. However, neither of these eventuated, and instead the Alaska meeting between Trump and Putin concluded with a rather disappointing non-eventuality, with very little being achieved to bring the Ukraine-Russia conflict towards a peaceful resolution.

The structural obstacles to peace

While many commentators and officials frame peace and a ceasefire in Ukraine as an easy task (even Donald Trump claimed he could end the war in under 24 hours), the reality is that there are deep structural barriers making a diplomatic end to this crisis unlikely at best, and impossible at worst.

Firstly, both belligerents view the other as a fundamental threat to their survival, leaving little incentive to halt hostilities. Since independence, Ukraine has feared Russian aggression and, understandably, the prospect of being subsumed into a greater Russian sphere of influence. As John Mearsheimer has put it, when you live next to a “gorilla,” there are strong incentives to seek powerful external security guarantees. This logic explains Ukraine’s desire for NATO membership.

For Russia, however, NATO expansion into Ukraine represents the “brightest of red lines, ” to borrow the words of William Burns, former U.S. ambassador to Russia and CIA director. The idea of NATO missiles and conventional forces stationed near Kyiv is seen as intolerable, not only by Putin but by the Russian elite more broadly. Their anxiety is rooted not just in present geopolitics but in history; Russia has been invaded from the West three times in the past two centuries, by Napoleonic France, Imperial Germany, and Nazi Germany. Each of these invasions threatened the very survival of the Russian state. Western observers often respond by insisting that NATO is “purely defensive” and that Russia has nothing to fear. Yet international politics rarely operates on how one side views itself. One state’s defensive alliance is another’s offensive threat. Whether the West sees itself as benign or not, Russia perceives NATO expansion as a strategic threat. This threat is not just a figment of Vladimir Putin's imagination. NATO enjoys nearly a four to one advantage in manpower, ships, aircraft and armoured vehicles. Any durable settlement must recognize that both Ukraine and Russia have legitimate security concerns, however uncomfortable that reality may be.

Secondly, the two sides are not negotiating toward the same objective and final outcome. Ukraine, backed by Europe and the US, is pursuing a ceasefire, a temporary pause in fighting that allows Kyiv to regroup and reinforce its defenses without conceding territory. President Zelensky has made clear his unwillingness to formally cede land to Russia as part of any settlement. Russia, by contrast, seeks a comprehensive peace deal. For Moscow, this means Ukraine renouncing forever any bid to join NATO and accepting the role of a neutral buffer state. Crucially, it would also require Kyiv to acknowledge Russia’s control over much of four occupied oblasts: Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, Luhansk, and Donetsk.

Thirdly, and this is a point often overlooked by Western analysts, the United States is not a neutral actor but a co-belligerent party in this conflict. Washington has trained Ukrainian forces, supplied them with advanced weapons, and provided battlefield intelligence. The US has done everything short of deploying its own troops in the conflict. Given this reality, the idea that Washington could act as an impartial mediator is laughable. No party so deeply invested in one side’s military success can claim to be an honest broker for peace. This is why earlier negotiations between Ukrainian and Russian delegations were hosted in Turkey, a largely non-aligned player in the current conflict.

These clashing perspectives and objectives, make the prospect of a negotiated settlement highly unlikely.

The inescapable reality on the ground

The reality is that Russia is winning this war and that reality is not likely to change anytime soon. As the famous war theorist Carl von Clausewitz proclaims, “war is the continuation of politics by other means”. Russia by virtue of their battlefield and military position, is in control politically. As President Trump shrewdly exclaimed to President Zelensky in their now infamous White House meeting, the Ukrainians simply "don't have the cards”.

As a result, Ukraine and the wider West have little room to set conditions in negotiations. Yet, many Western leaders continue to insist that Ukraine’s objective should be to reclaim all lost territory, including Crimea, a rhetoric that President Zelensky also echoes. That stance is no longer rooted in strategic reality but in delusion and propaganda. While this argument carried some weight early in the conflict, or even in mid-2023 during Ukraine’s much-anticipated counteroffensive, the outlook by mid-2025 is completely different.

Russia is winning on the battlefield. It may not be gaining territory at the pace once predicted, but it might not need to. With clear advantages in manpower, manufacturing base, and munitions, Moscow can sustain a long war of attrition. Ukraine, increasingly, cannot.

There is also a moral dimension to this. If Ukraine cannot realistically defeat Russia on the battlefield, then prolonging the war further means condemning thousands more soldiers to die for an unwinnable cause. Ukraine has fought with determination and exceeded the expectations of most analysts and security experts. But now the time has come to accept that “fighting to the last man” is rhetoric, not reality.

International politics often comes down to choosing the least bad of two terrible options. Handing over four oblasts, roughly 20 percent of Ukrainian territory, is undeniably a terrible outcome. But the alternative could be even worse: Russia pressing further, seizing Odessa, and rendering Ukraine a landlocked state without access to the Black Sea. Potentially, even taking control of Kiev and implementing a puppet government, similar to that in Belarus. As John Mearsheimer has observed, the choice before Zelensky is not between victory and defeat, but between a “rump state” and a “dysfunctional rump state.” Time will tell which one he chooses.